Can Kosovo's youth groups overcome the ethnic divide?

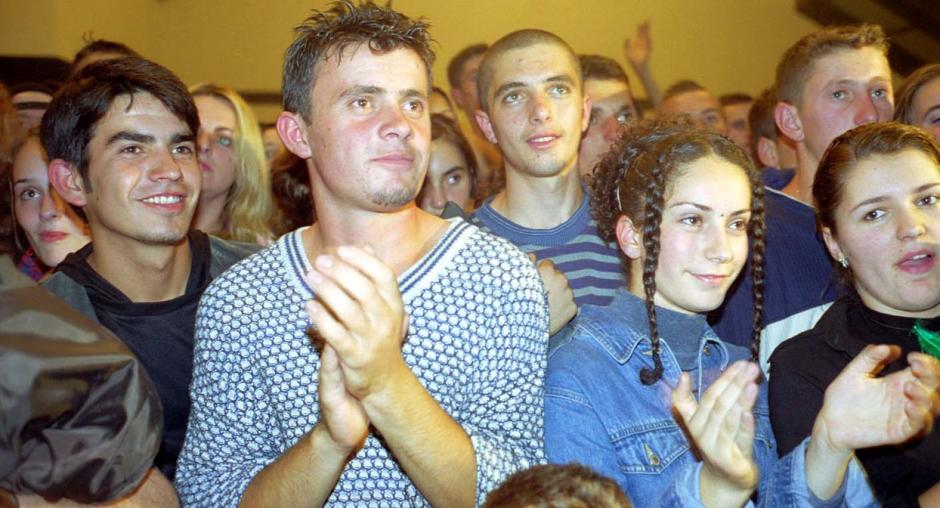

Young people dancing and singing together at an open-air disco is not an unusual sight but, in this particular instance, it was. The social gathering in question was taking place at the OSCE-run police school in Vushtrri / Vucitrn. And the one hundred or so revellers came from across Kosovo's ethnic divide.

Little socializing

The reality of life in Kosovo today is that Kosovo Albanian and Kosovo Serb young people don't socialise together on a regular basis. Because they can't. The security situation doesn't allow it. The sins of the past don't allow it. The communities themselves and even parents don't allow it.

It's a sad reflection of just how bad things are when two young women friends - one Serb and one Albanian - have to go to a town where neither is known in order to do something as normal as go to a cafe together. Sad, too, that a police school should be the only place where a multi-ethnic group of 16 to 25 year olds can spend time together in safety. The school, of course, is a multi-ethnic environment. The Kosovo Police Service now has officers from all communities. Both are practically unique phenomena in Kosovo.

Kosovo has the youngest population in Europe - about 60% of its people are under the age of 25. The event at the police school was certainly one of the most important gatherings of young people to be held here for several years. The aim was to help them get to know each other, start networking and looking at the future of the youth NGO sector in Kosovo. The other aim was to discuss issues they had identified as important and what they could do about them - issues like insecurity and violence, drugs and unemployment. In other words, problems they had in common, no matter what ethnic community they came from.

North and South Mitrovica Divide

As they split up into regional working groups for a brainstorming session, Agim from Mitrovice south bumped into a young Serb man from Mitrovica north. They got talking and decided there and then that their two youth groups should try and get together. They discovered they were both concerned about drug abuse. "There are a lot of young people spending time just walking around the streets. There is no work and nothing for them to do. We both think it's inevitable that drug abuse will become a bigger problem on both sides of the city", said Agim. When asked how they would manage to meet up when neither group can cross the bridge, Agim was less sure. But he was determined. "It won't be easy. We will need help from organizations like the OSCE. But we exchanged telephone numbers so we can keep in touch and figure something out."

Like Anna, the young Serb woman whose Albanian friend occasionally crosses the River Ibar to meet her for coffee, Agim also had friends on the other side. They, though, haven't managed to keep in touch. "War is war," he shrugged. "What can we do?" That was a sentiment echoed by Serb youngsters too.

Others, meanwhile, have been caught in the middle. 16-year-old Ramadan is from the Ashkaelia community in Rahovec/Orahovac. The Ashkaelia and the remaining Serbs there are confined to an enclave. He speaks Albanian but only a little Serbian. Before the conflict, Ramadan went to school with Albanian and Roma children. They used to play football together. He'd like to see his Albanian friends again but, he said, they don't want to see him. He said his former schoolmates believe his community was against theirs during the conflict. "But I am on no-one's side," said the quiet young man in the football jersey.

Establishing contact

Nenad is hemmed in on all sides. He lives in the Serb village of Gorazdevac, 6km from Peja/Pec. But he hasn't been able to move outside his small enclave for two years. Almost all the young people in the village are unemployed. "What is not a problem for young people in my village?" he said.

A week before the youth congress, the OSCE democratisation officer in the area brought a young Albanian out to Gorazdevac to meet him. Gazmir is in a youth group in the town of Peja/Pec. They talked about the congress and, when asked if they would be prepared for their youth groups to co-operate, they both said yes. They have no idea yet what sorts of projects they might link up on but it's a start. Gazmir said he found the initial meeting difficult but he appreciated Nenad's welcome. When they arrived at the police school, Gazmir said Nenad came up to him when he saw him there and greeted him.

A small step but contact has been established. There was a degree of hesitation, possibly reluctance on both sides. But also a willingness to consider the possibility of further contact and co-operation. Steps like that, however small, however localised, are vital if the process of reconciliation and of rebuilding trust is to really begin in Kosovo.